Hope beneath toxic waters: South Australia’s worst algal bloom and the power of community

- Morgane RGM

- Nov 15, 2025

- 4 min read

South Australia’s worst algal bloom on record

The water was green. Not the turquoise that divers know so well, but a toxic, unhealthy hue that clung to the shoreline. Beneath the surface, movement slowed on the beach at Port Noarlunga, lifeless fish lay tangled in seaweed. Below, rays, octopus, and sea dragons drifted in the swell, silent witnesses to something deeply wrong.

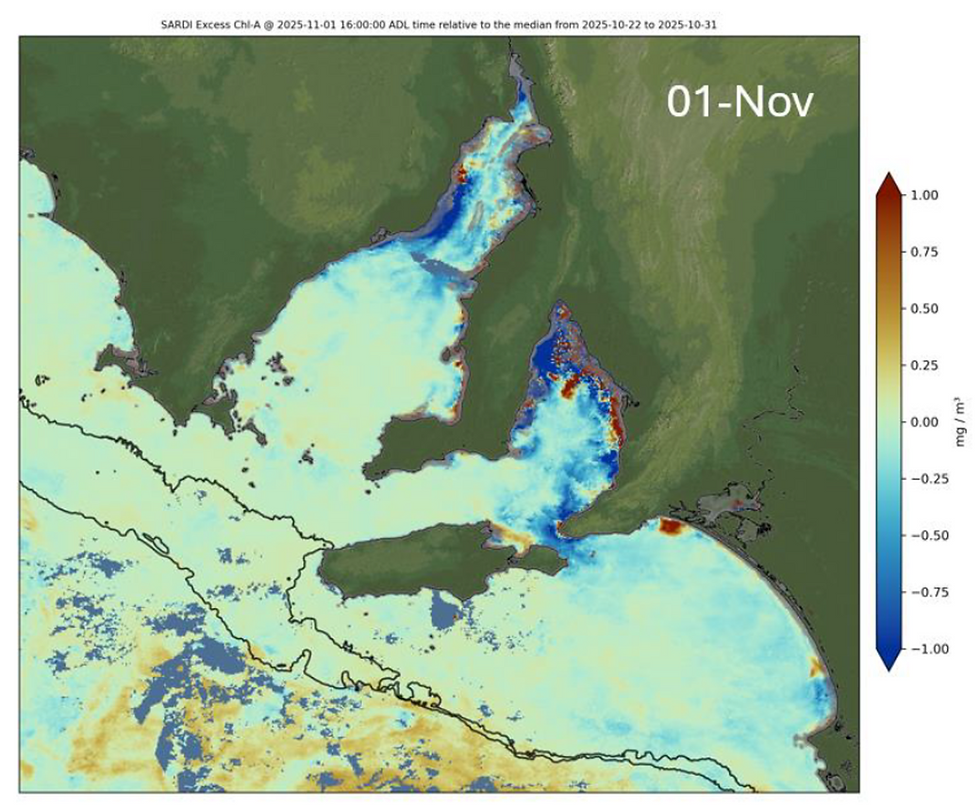

By early winter 2025, the ocean along South Australia’s coastline had changed beyond recognition. What began as an isolated bloom in the south-east spread quickly across more than 4,500 square kilometres of coastline, sweeping over the Fleurieu Peninsula, Kangaroo Island, Yorke Peninsula, and deep into Spencer Gulf and the Eyre Peninsula.

The culprit was microscopic. Originally thought to be Karenia mikimotoi (a toxic algae known worldwide for its persistence and power to suffocate marine life). The bloom was later identified as a dangerous mix of several Karenia species, some even more harmful. One in particular produces brevotoxins, which are neurotoxins known to disrupt nervous systems in marine life.

Yet the roots of this bloom ran far deeper into warming oceans, nutrient imbalances, and a rapidly shifting climate. A new discovery has also raised concern: one of the toxin-producing species appears to be common in cooler waters. This finding is not yet fully verified or understood, but researchers are now investigating it further.

A diver’s perspective

For Sarah Franke - a marine biologist and industry engagement lead at Divers for Climate (DFC) - the devastation felt personal.

Both her parents were divers, and she’d grown up among reefs and tide pools, learning to read the water’s moods before she could name them. She studied marine biology with a focus on coral ecosystems, and later trained as a divemaster in Indonesia’s Lembongan, resulting in witnessing coral bleaching firsthand on the Great Barrier Reef in Airlie Beach.

When reports of dead sea dragons and green foam began surfacing in May, Sarah and the DFC team headed south to witness the situation for themselves a bit later in August.

“It was confronting,” she recalled. “Even the fish that weren’t dead were acting strangely. The water had this green foam; thick, toxic, with a smell that burned your throat. We found weedy sea dragons washed up on the beach, it was unlike anything I’ve ever seen.”

Their dives revealed a grim reality: the algal bloom extended to depths of at least 40 metres, and possibly deeper. It wasn’t just a surface event, it had infiltrated the heart of the marine ecosystem.

🎧 Listen to Sarah’s personal take on the Algal Bloom on Spotify

Communities under strain

The damage wasn’t only underwater. DFC’s Algal Bloom Case Study documented a chain of impacts reaching far beyond the shoreline.

📄 Read the Case Study for a more detailed view

Economic: Dive tourism, seafood industries, and coastal small businesses all suffered. Operators cancelled trips, fishers stayed ashore, and visitors vanished from once-bustling coastal towns.

Health: Onshore, residents reported respiratory irritation, headaches, and eye pain from airborne toxins. On windy days, people kept their windows shut and their children inside.

Mental health: For many, the ocean had always been a place of peace, a refuge from daily pressures. Now it was a source of anxiety and grief. Dive shop owners spoke of sleepless nights, uncertain income, and a deep sense of loss.

People are losing not just their livelihoods, but their sanctuary.

Slow response, fragile solutions

By the time authorities announced a $28 million recovery package, much of the damage had already been done. Operators described confusion and delays, unclear communication, and a lack of long-term vision.

“The system is weak,” one DFC report noted. “Limited support, poor monitoring, and no clear management framework are holding us back.”

Among the few hopeful measures was an experimental bubble curtain; a wall of air bubbles designed to protect cuttlefish eggs from the toxins. Innovative, yes, but costly, temporary, and far from a real solution.

There was also a growing sense that South Australia was being overlooked.

“If this were happening in Sydney Harbour,” Adelaide locals said, “the response would’ve been very different.”

A warning for Australia’s oceans

The 2025 algal bloom was more than a local tragedy. It was a warning flare for Australia’s oceans.

Across the country, divers and scientists were seeing the same patterns repeat: coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef and Ningaloo, shifting species ranges along temperate coasts, and the steady disappearance of kelp forests in the south.

Each of these losses chipped away at ecosystems that underpin tourism, recreation, and cultural identity. The 2024–2025 marine heatwave had already been declared the most widespread and severe ever recorded globally: a symptom of oceans under stress.

The call for collective resilience

If there was one thing that survived the bloom, it was solidarity.

Divers, operators, and local communities began sharing data and speaking out together. For many, it was their first taste of what true climate resilience could mean: being informed, connected, and active in shaping a sustainable future.

DFC encouraged divers to keep visiting unaffected sites like Rapid Bay and Second Valley to support local operators, and to sign a collective statement calling for stronger ocean protection and climate action. So far, more than 40 dive shops and 100 individuals had joined.

“This is not the time to give up,” Sarah said. “It’s the time to come together and do everything in our power to protect what we love. Hope is not lost. Through collective action we can create waves that ripple through communities and reach the places where decisions are made.”

Her words carried both urgency and faith, echoing through a community that had seen too much loss to turn away.

The sea will remember

When the waters finally clear, the scars will remain. Etched into the reefs, the memories of those who dove through the bloom, and the stories shared in its aftermath. But beneath the grief lies something steady: the will to keep protecting what’s left, and to rebuild what’s been lost.

In the end, perhaps that’s what resilience really means. Not blind optimism, but choosing to return to the water even when it breaks your heart.

Comments